Odilion Redon (1840-1916) was an intriguing artist. Working

through the turn of the century, he often engaged with the nineteenth-century

fascination with ideas of evolution coupled with fears of degeneration. With the

awareness of Charles Darwin’s theories of how man developed also came a fear

that perhaps mankind could ‘evolve’ into something less intelligent. The

medical sciences were advancing in their understanding of hereditary

conditions and so a kind of inversion of Darwin’s theories where the defects of

an individual were passed on rather than their strengths became a fear that was

felt by many.

Redon made his name through his Noirs drawings. Entirely monochrome, these works explored ideas of

botany and evolution, whilst always giving the ‘creatures’ a human and

empathetic quality. From the 1890s, Redon began displaying works in colour

(previous to this he had only exhibited his Noir

works). These pieces engaged more with spiritual ideas. Around him were artists

and radical thinkers of the age who were slowly converting to Christianity, and

who turned their evangelistic pressures onto Redon himself. In the 1890s

Joris-Karl Huysmans, author of the controversial ÁRebours and friend of Redon converted, while the artist’s friend

and patron Gabriel Frizeau put continual pressure on Redon to convert to Catholicism.*

Through his production of the 1890s it could be argued that Redon was working

out his interest in religion and attempting to reach his own conclusions about

a spiritualism that he could engage with. Eventually Redon came to believe that

the Eastern religions of Buddhism and Hinduism had more ‘truth’ in them than

the conservative Christianity of the West; however, in all of these

philosophies it was their other-worldly aspects and spirituality which

attracted him, rather than their moralistic approach to life.

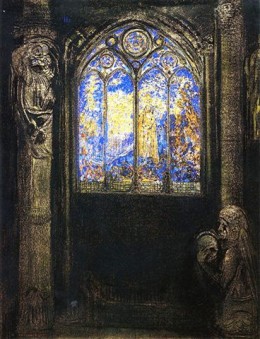

Le Grande Vitrail

(1904, another work in the Orsay in Paris) seems to me to encapsulate this

sensibility in Redon. This work draws

attention by the brilliant blues of the glass in the large stained-glass window

that is the subject of the work. Redon’s colour pastels are characterised by a luminosity

which immediately gives them a transcendental spiritual element; these works

are not about the physical and material, they ask us to consider the unseen

truths in the world around us. In Le

grande vitrail Redon combines the dark materiality of his Noirs with the transcendence of his

colour images. As the viewer looks beyond the attractive colour in the window,

the dark themes of the ecclesiastical interior come into focus. It is almost as

if Redon is attempting to trick the viewer to engage with his dark works: the

creatures that he includes carry a sinister gothic horror.

Kneeling in the foreground are two children. We believe them

to be children by their size and proportions, and the way in which they cling

to another, as infants do. However, Redon replaces both the children with

metaphors: one has a grief-stricken face which appears somehow older than her

body suggests, and from her back are the suggestion of angelic wings, while the

other’s head is replaced by a hollow skull. These beings represent a kind of

half-life. They foretell of creatures in the Afterlife: what they will become.

Given the contemporary interest in disease and decay, it could be assumed that

the hopelessness of these beings relates to physical defects; however, the

juxtaposition in this work with heavily Christian spirituality suggests

something more philosophical.

Diagonally across the image from the two infants is a

carving in the stone of the pillar to the side of the window. This presents a

Madonna cradling the infant Jesus. She curls from the top of her spine so her head

covers the child in a protective embrace. This scene exists outside of the

safety of the heavenly realm which is presented in the window, and there is the

sense that the Madonna – finding herself in the dark earthly realm – is

desperate to protect her son from the threat around. This threat exists in the

shadowy corners of the periphery of the work. As with James Ensor’s work Redon

hides a series of disturbing faces amongst the stonework of the church.

Gargoyles look down upon the scene from the top of the tall pillars, and where

the decoration at the top of the Corinthian columns either side of the window

should be gentle curls, instead Redon draws in a group of skulls. Below the

window is a tomb, and at the top right the figure of a man silently and

morbidly views the scene, unable or unwilling to intervene by moving past the

pillar which segregates him from the main part of the composition.

Meanwhile, just off-centre in the window itself stands the

man Christ. He appears passive with his hands crossed in front of him, and his

head turned slightly heavenward. Around him a few figures kneel and gaze up at

him, while the brilliant blue of the background is offset by Redon’s

characteristic metallic gold, suggesting clouds of angels behind him. This

window does not seem to present the earthly realm; it may be a heavenly

setting, or the collision of heaven and earth that the Bible foretells. Either

way it is wholly inaccessible to the material world that Redon presents around

the window.

This image could be read as a presentation of hope and

redemption in the promise of salvation through Christ; however this

interpretation would deny the clues that Redon leaves that suggest something darker. Neither the carved Madonna, nor the crouched infants in the

foreground engage with the window. They do not see the figure of Christ as a

promise of redemption. Instead this work seems to suggest that the earthly

world is too damaged for the hope of Christian salvation to apply anymore. The

children are already becoming damaged creatures of the afterlife, despite their

innocence (which is suggested by the wings). Disease and decay – symptoms of

the fallen world – have taken hold of contemporary society; how can the

heavenly scene in the window have any relevance to them. The brilliant colours

of the stained glass allow no light in to shine upon the scene within the

building.